Note: This article was updated on Oct. 4 with additional recommendations.

It’s generally a bad idea to write a book.

First, it takes time away from other things you could be writing. And second, it freezes your ideas in time, such that you can’t easily take them back or tell readers, “Wait, no! I’ve changed my mind!” later on. Even worse, as Gwern wrote in a recent essay, is that:

“A book commits you to a single task, one which will devour your time for years to come, cutting you off from readers and from opportunity; in the time that you are laboring over the book, which usually you can’t talk much about with readers or enjoy the feedback, you may be driving yourself into depression.”

And what happens when a writer finally finishes their book? Well, that’s when their true task begins, for they must pray and plead with people to buy it. Despite a writer’s best efforts, however, odds are that very few people will read it.

About 90 percent of books sell fewer than 1,000 copies. Half of all published books sell less than one dozen copies. Most best-selling books are written by celebrities and politicians (or their ghost writers) and existing authors with large, established audiences — Michelle Obama, Brandon Sanderson, Stephen King…that kind of thing.

Just because a book sells poorly, or goes out of print shortly after it’s published, does not mean it’s not a good book. The market does not always have good taste! I suspect there will always be an eager audience for books by Nick Lane and Ed Yong, but many other excellent writers fly ‘under the radar.’

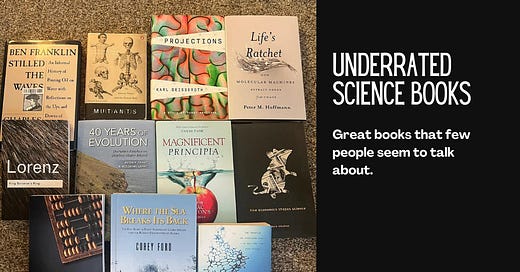

I’d like to remedy this situation — just a bit! — by sharing some of my favorite ‘underrated’ science books. I selected these books simply because I enjoyed reading them and have never heard others bring them up in conversation. Note that this is not a ranked list, because people don’t seem to like those.

Please share your own underrated book recommendations in the comments below.

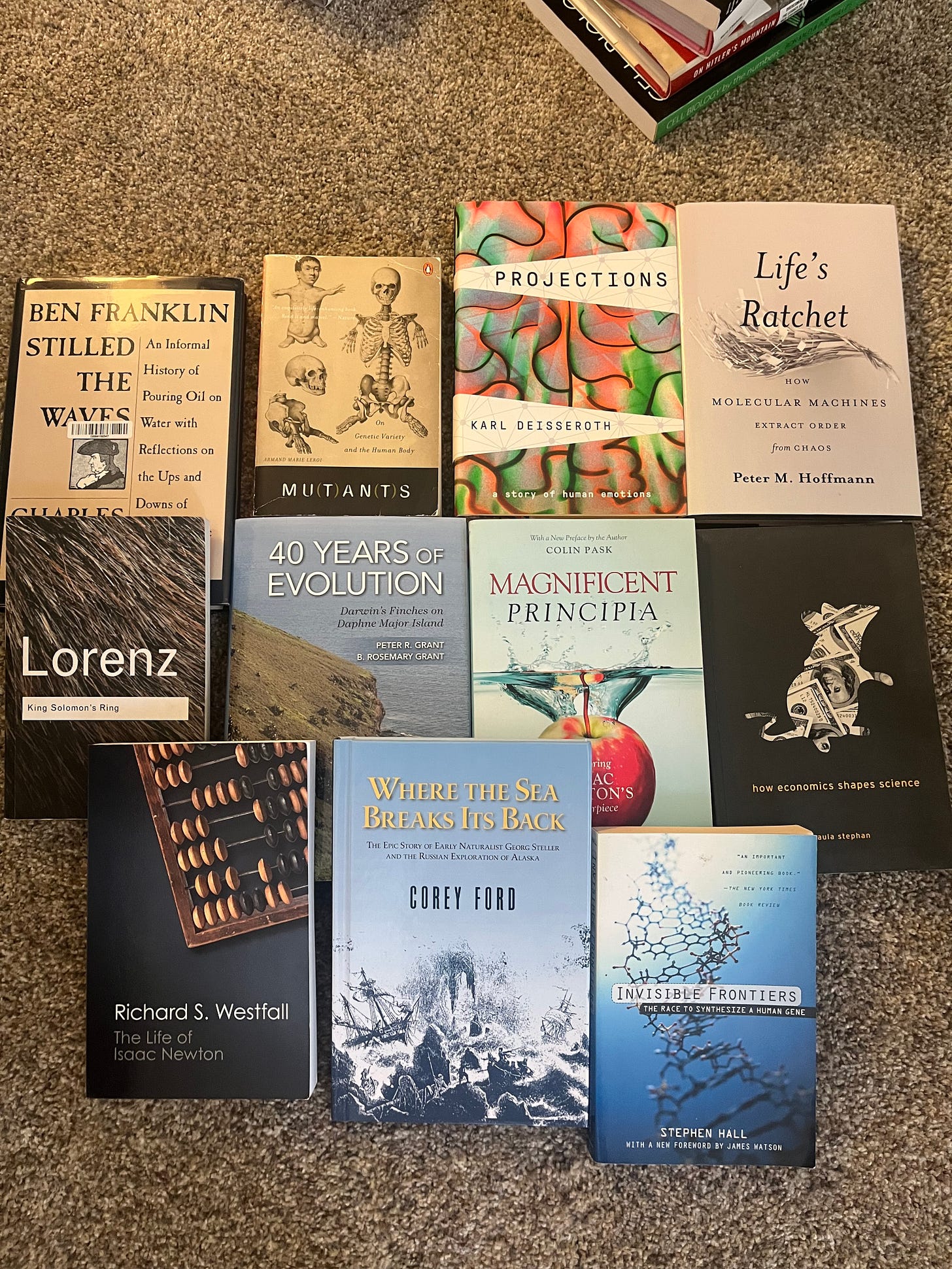

40 Years of Evolution, by Peter & Rosemary Grant. This is my favorite book in the bunch. It is written by two Princeton scientists — a husband and wife duo — who spent several months on Daphne Major, an island in the Galápagos, every year for forty years. While there, they captured finches and measured their beaks, observing evolution in real-time. It’s absolutely brilliant and highly underrated.

Ben Franklin Stilled the Waves, by Charles Tanford. This book recounts the story of Benjamin Franklin's experiments with oil on water (I wrote about it here). The gist is that he dropped some oil on a pond in Clapham Common, London, and noted how it “stilled the waves.” In the late 1800s, Lord Rayleigh repeated Franklin’s experiments and made more precise measurements. By dividing the volume of oil by the area it covered upon the water’s surface, Rayleigh was able to calculate the oil’s thickness and, in doing so, estimate the length of a single molecule. His estimates were off by just 2 percent. I love this book because it shows how simple experiments and mathematics can, together, reveal the invisible by measuring the visible.

Invisible Frontiers, by Stephen S. Hall. This is the most readable book I’ve found about biotechnology’s formative years. It covers the invention of recombinant DNA and the race between academic scientists in Massachusetts, California, and a startup company called Genentech to create human insulin using engineered microbes.

Life's Ratchet, by Peter M. Hoffmann. This book is subtitled, “How molecular machines extract order from chaos.” Hoffmann does a brilliant job explaining how proteins convert electrical voltage into motion, or how ‘tiny ratchets’ transform random motion into ordered outcomes. This is an accessible introduction to biophysics, and is filled with incredible statements. For example, while describing a protein that carries cargo through a cell, Hoffmann explains that 1021 of them would generate as much power as a typical car engine…

Yet, this number of molecular machines barely fills a teaspoon—a teaspoon that could generate 130 horsepower!

Projections, by Karl Deisseroth. A brilliant modern take on neuroscience, written by one of its foremost practitioners. Deisseroth is a co-inventor of optogenetics, a technique that uses pulses of light to trigger action potentials in the brain. In this book, he explains how the method works and how it’s being used to map neural circuits. Deisseroth also draws from his experiences as a physician, using patient stories to illustrate how neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases operate at a mechanistic level. A worthy successor to Oliver Sacks.

Where the Sea Breaks Its Back, by Corey Ford. First published in 1966, this is an adventure book first and a science book second. It chronicles the expedition of naturalist Georg Steller and Vitus Bering in the 18th century. Despite preparing to set sail for Alaska over a ten-year period, Steller spent just ten hours in Alaska. The crew later shipwrecked on an island for about a year and many men died. Throughout the voyage, Steller writes about sea otters near the Aleutian islands (their populations later collapsed) and gives detailed anatomical descriptions of sea-cows, which were later named after him. This book is reminiscent of Endurance, about Shackleton’s escape from Antarctica, but is more scientifically-driven.

The Life of Isaac Newton, by Richard Westfall. An accessible portrait of Newton, covering his contributions to optics and mathematics, but also his lesser-known pursuits in alchemy and theology. This is really the first book that made me appreciate Newton’s genius; all the others seem to overcomplicate the subject.

Magnificent Principia, by Colin Pask. The only book that actually helped me understand Newton’s Principia Mathematica. Divided into seven parts, Pask first describes Newton’s background and character, then dives into his scientific approach and explains what classical mechanics says about the world around us. Notably, there are lessons in here about the ‘risk-averse’ nature of modern science as opposed to the freewheeling methods that often governed discoveries in Newton’s day.

How Economics Shapes Science, by Paula Stephan. This book paints a detailed picture of science funding in the United States. It is so detailed, in fact, that it became outdated shortly after its publication in 2012. Still, I think this book is an essential read for scientists because Stephan exposes how funding, incentives, and economic pressures influence the direction and nature of scientific inquiry. This is the first book where I really felt like I understood how science works at a meta-level, and how we might be able to make it better (shortly after reading it, I went to work at New Science.)

Other great books not on this list:

Mutants by Armand Marie Leroi

King Solomon’s Ring by Konrad Lorenz

Gödel, Escher, Bach by Douglas Hofstadter

The Demon Under the Microscope by Thomas Hager

The Vital Question by Nick Lane

Gene Machine by Venki Ramakrishnan

Edison by Edmund Morris

Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age by W. Bernard Carlson

The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf

The Billion-Dollar Molecule by Barry Werth

Stories of Your Life and Others (sci-fi) by Ted Chiang

The Wizard and the Prophet by Charles C. Mann

Laws of the Game by Manfred Eigen

The Lives of a Cell by Lewis Thomas

The Genesis Machine by Amy Webb & Andrew Hessel

Book recommendations from Twitter:

How Life Works by Philip Ball

The Eighth Day of Creation by Horace Freeland Judson

Power, Sex, Suicide by Nick Lane

Cathedrals of Science by Patrick Coffey

Longitude by Dava Sobel

Beyond the Hundredth Meridian by Wallace Stegner

Trilobite by Richard Fortey

Altered Fates by Jeff Lyon and Peter Gorner

Gene Dreams by Teitelman

Breath from Salt by Bijal P. Trivedi

Alchemy of Air by Thomas Hager

— Thanks for reading.

My recommendations (can't say they are necessarily underrated) :

Time, Love, Memory by Jonathan Weiner - Profiling Seymour Benzer

Beak of the Finch also by Jonathan Weiner - About Peter and Rosemary Grant! I hadn't realised that they also had written a book.

Lab Girl by Hope Jahren