Estimating the Size of a Single Molecule

How Ben Franklin and Lord Rayleigh used little more than oil and water to calculate a molecule's size.

Many decades before the discovery of x-rays and the invention of powerful microscopes, Lord Rayleigh calculated the size of a single molecule. And he did it, remarkably, using little more than oil, water, and a pen. His inspiration was none other than Benjamin Franklin.

Sometime around 1770, while visiting London, Franklin became intrigued by a phenomenon he had observed during his transatlantic voyage. Specifically, he noticed that when ships discarded greasy slops into the ocean, the surrounding waves would calm. This ancient practice of oiling the seas to pacify turbulent waters was known to the Babylonians and Romans, but Franklin decided to investigate further.

On a windy day in London, he walked to a pond on Clapham Common. Carrying a small quantity of oil — "not more than a Tea Spoonful," according to his diary — Franklin poured it onto the agitated water. The oil spread rapidly across the surface, covering "perhaps half an Acre" of the pond and rendering its waters "as smooth as a Looking Glass." Franklin documented his observations in detail; they can be read today on the Clapham Society's website.

Franklin's oil drop experiment, of course, was just one in a long line of his “amateur” science experiments. He was also the first to demonstrate that lightning is electrical in nature (via his famous kite experiments), and he charted the Gulf Stream’s course across the Atlantic ocean, noting that ships traveling from America to England sailed quicker than those going the opposite direction. His experiments at Clapham Common are not nearly as well-known.

But Franklin was a careful experimenter, repeating his oil drop multiple times and taking notes each time. In his journal, he opined on how much oil might be needed to calm various areas of ocean (he was thinking specifically about applications for the Royal Navy) but never grasped the molecular implications of his experiments. It wasn't until more than a century later that Lord Rayleigh, whose real name was John William Strutt, revisited Franklin's experiment with a brilliant new perspective.

An academic at the University of Cambridge and a baron by title, Rayleigh was renowned for his work in physics. The Rayleigh number, a common parameter used to describe the flow of water, is named for him; as is Rayleigh scattering, which explains how photons diffuse through the atmosphere and color the sky blue. Rayleigh also discovered the noble gas, Argon, earning a Nobel Prize for it in 1904.

But a little experiment that Rayleigh performed in 1890, inspired directly by Franklin's observations, is not nearly as well-known.

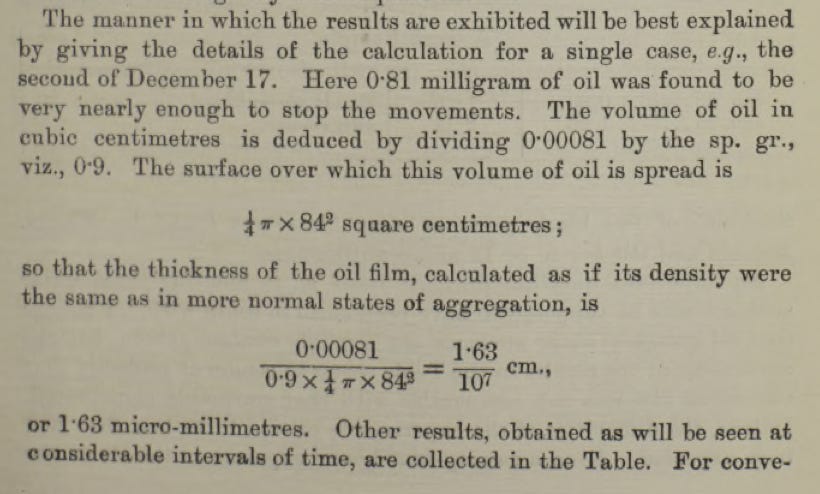

Rayleigh carefully measured a tiny volume of olive oil — 0.81 milligrams, to be exact — and placed it onto a known area of water. The oil quickly spread out and covered an area, which Rayleigh precisely measured. And then he did something that Franklin never thought of: Rayleigh divided the volume of the oil by the area it covered, thus estimating the thickness of the oil film. Assuming that the oil formed a single layer of molecules — a monolayer — then the thickness of the oil film is the same thing as the length of one oil molecule.

This is how Lord Rayleigh became the first person to figure out a single molecule’s dimensions, many years before anyone could see such molecules.

Here is his equation:

Rayleigh’s final result was 1.63 nanometers. Olive oil is mainly composed of fat molecules called triacylglycerols, and modern measurements show that they measure about 1.67 nanometers in length, thus implying that Rayleigh’s “primitive” estimates were off by just 2 percent. His original paper detailing the experiment can be found here.

I love this story because it shows, at least anecdotally, how deep scientific insights can emerge from the simplest of experiments. It's a testament to the idea that you don't always need sophisticated equipment to unlock the secrets of nature — sometimes, all it takes is a drop of oil and a bit of ingenuity.

For those interested in delving deeper into the history of these oil drop experiments, Charles Tanford's book, Ben Franklin Stilled the Waves, offers a much deeper exploration.