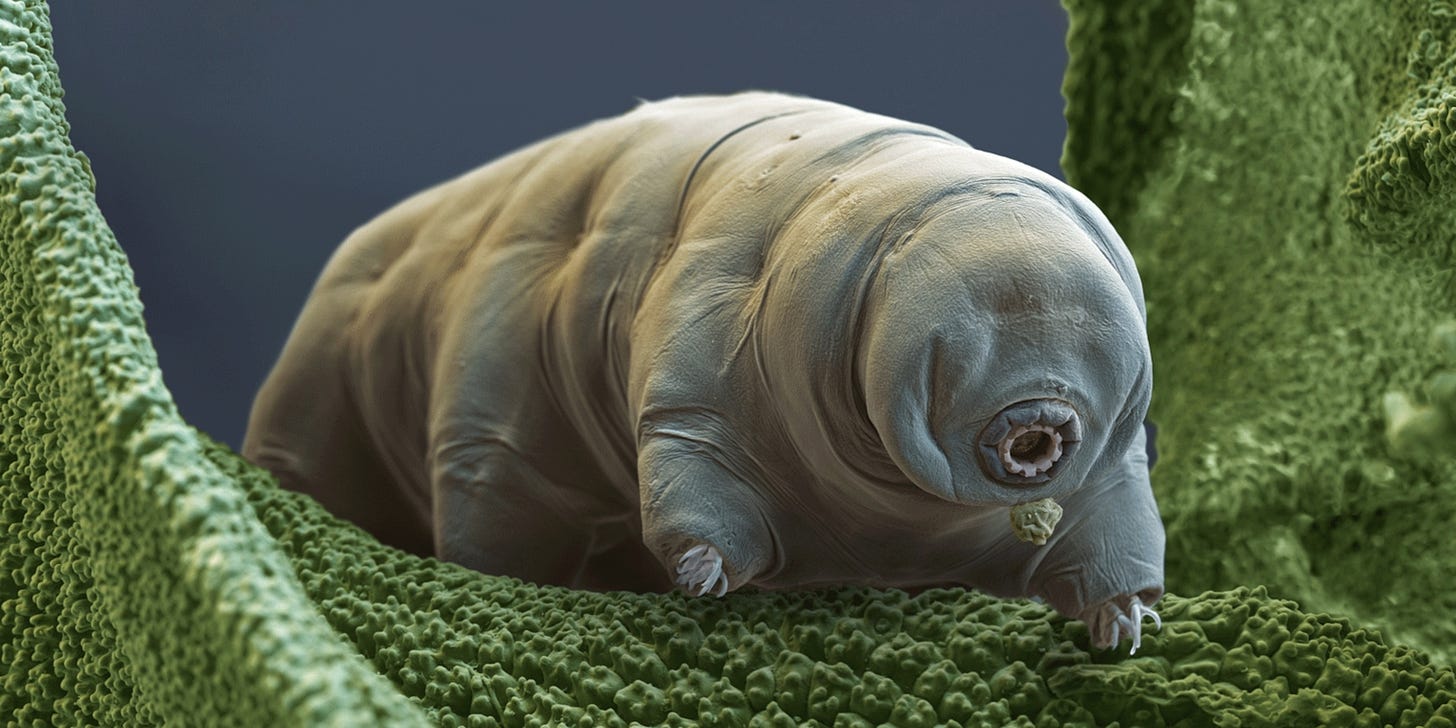

A few months ago, I saw some claims online that tardigrades—also called water bears—can survive for up to 30 years without food or water.

Naturally, I was curious about the veracity of this statement, so I did a few Google searches and followed breadcrumbs back to the original reports. A Quora poster had previously written that they first heard this claim from a National Geographic article. But that Nat Geo article had a paywall, and when I finally got around it, all it said was:

Tardigrades belong to an elite category of animals known as extremophiles, or critters that can survive environments that most others can't. For instance, tardigrades can go up to 30 years without food or water. They can also live at temperatures as cold as absolute zero or above boiling, at pressures six times that of the ocean’s deepest trenches, and in the vacuum of space.

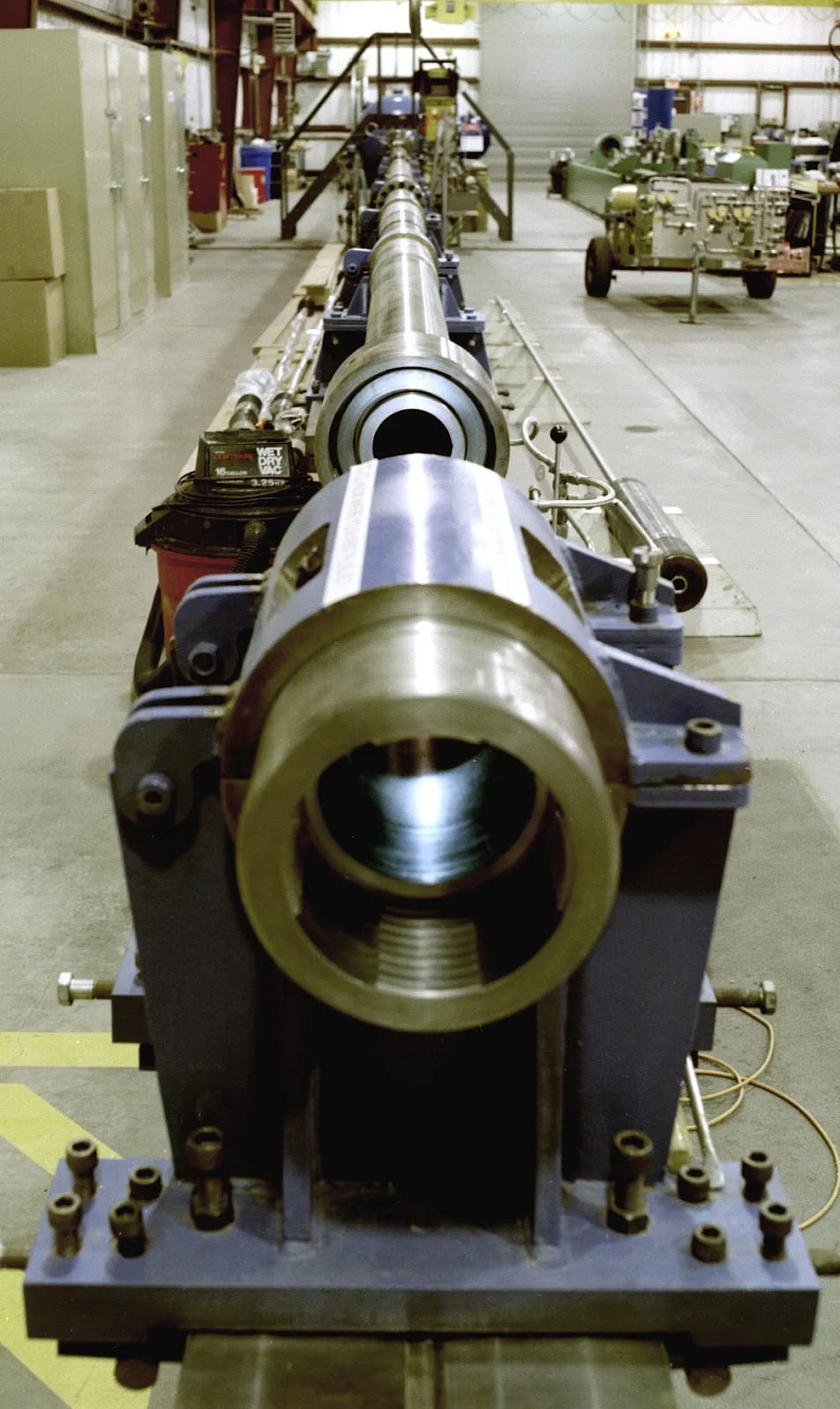

The article didn’t include a hyperlink or any other citation for the “30 years” claim. (Also, they didn’t mention the coolest tardigrade feat: that they can survive after we shoot them out of a high-speed gun, at speeds around 3,000 feet per second, and survive the impact!)

After a bit more digging, I found the original source: a 2016 research article that researchers published in an obscure journal called Cryobiology. In this study, Japanese scientists found tardigrades clinging to frozen moss, without food or water, that researchers had placed in a freezer 30 years prior.

Back in 1983, a scientist at the National Institute of Polar Research in Tokyo, named Hiroshi Kanda, traveled to the Yukidori Valley in eastern Antarctica and collected moss samples there. Kanda wrapped the moss in paper, sealed them in plastic bags, and then chucked them into a -20°C freezer. And there they sat, waiting, for the next 30 years.

In 2014, Kanda’s successors in Tokyo found these moss samples and removed them from the freezer. After thawing the moss for 24 hours, the scientists added some water to the moss and picked the samples apart with tweezers to search for living organisms. They found a tardigrade egg, in addition to two living tardigrades clinging to the moss, which they named Sleeping Beauty 1 and 2. There were also dead tardigrades, but the researchers did not report their numbers in this study. It’s therefore difficult to know what fraction of these animals actually survive in the freezer for 30 years. (Is it a rare or common occurrence?)

During the first few days, the living tardigrades moved around very slowly, if at all. But after a few days, both of the animals started moving and feeding on algae that the researchers fed to them. Sleeping Beauty 1 later laid 19 eggs, 14 of which hatched. The egg clinging to the moss also hatched, and the tardigrade that emerged later had babies of its own.

In other words, frozen tardigrades can actually survive for at least 30 years without eating or drinking anything — but only if they’re frozen first! This is one instance, it seems, where ridiculous-sounding claims on the Internet ended up being true. Most comments about this that I found on the internet, however, failed to mention the “frozen” part. It’s likely that (unfrozen) tardigrades can only survive a few weeks without food.

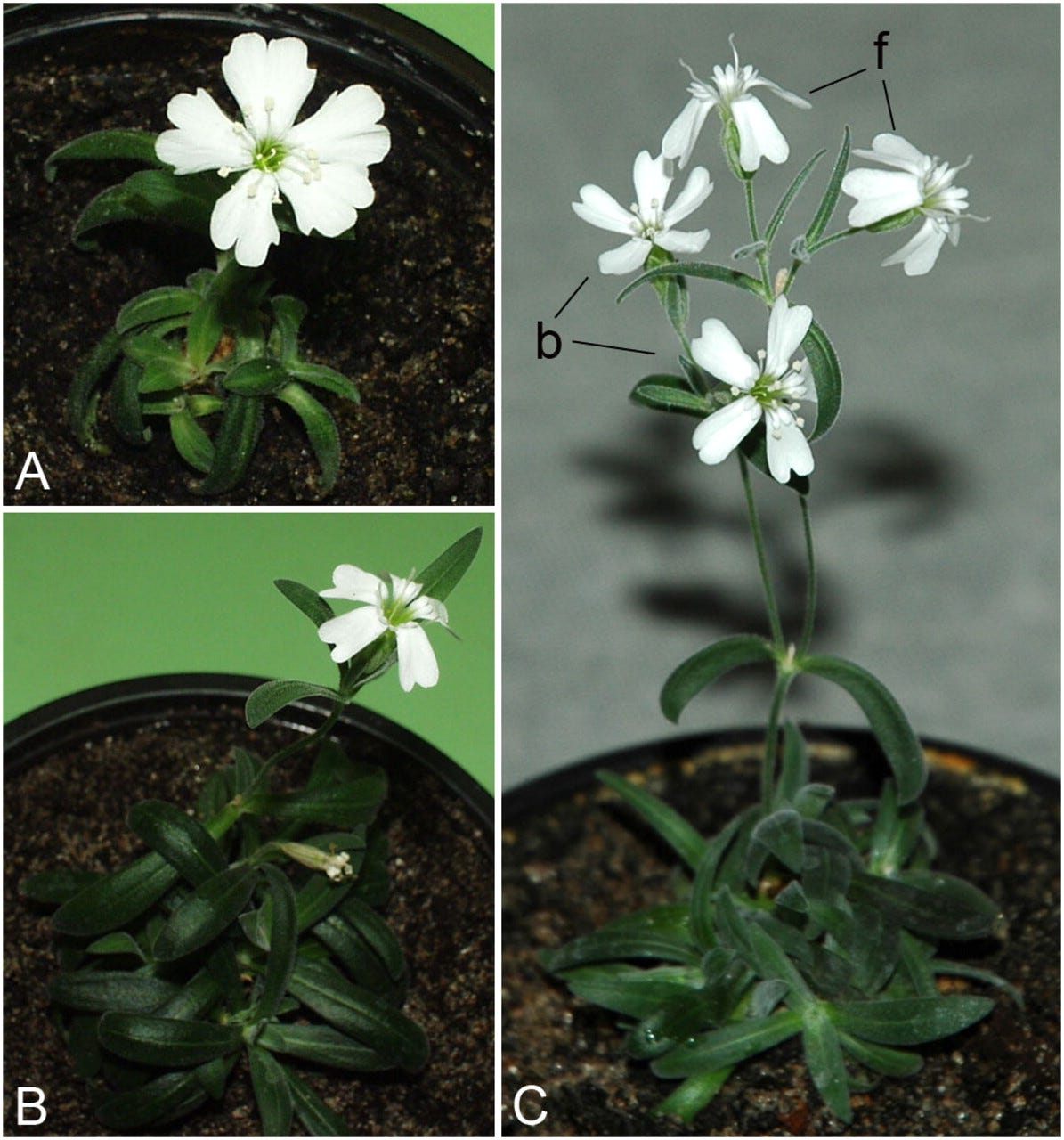

Tardigrades are not the only organisms that can survive for decades — or even thousands of years — in a frozen state. In 2021, scientists drilling in a remote Arctic location collected some permafrost and thawed it. A living rotifer emerged; it had been encased in the ice for at least 24,000 years, according to radiocarbon dating experiments. Other scientists in Siberia and Antarctica have also thawed out 400-year-old moss and a 32,000-year-old seed, both of which were viable. The seed regenerated and grew into a plant.

Tardigrades are able to survive for decades in ice because they enter a state called cryobiosis. When the animals sense that they’re surrounded by frozen water, they begin to shut down their metabolism and make cryoprotectants that change the freezing point of their internal tissue. Nobody knows exactly how, but tardigrades seem to be able to control ice formation so that their cells don’t get destroyed by crystals during freezing. Oddly enough, though, the tardigrades make all these changes without significant changes in their gene expression, suggesting that their “freeze-tolerance genes” are always switched on. It’s weird.

German naturalist Johann August Ephraim Goeze was the first to see tardigrades — or “little water bears,” as he called them — crawling upon a bit of moss, in 1773. A few years later, Lazzaro Spallanzani named them “tardigrada,” which means “slow steppers” in Italian. Scientists have been studying these little animals for several centuries, then, and it’s clear there’s so much we don’t understand about them, or how they survive and adapt to extreme conditions.

It also proves, at least anecdotally, that scientific discoveries can be made by innocuous actions, like thawing out some samples stuffed in the back of a freezer.