The world needs more essays about biology. So last month, I tweeted a link to one of my favorite essays (#1 below) and promised that I would continue to share an additional essay every day for the next 29 days. I titled the series, “30 Essays to Make You Love Biology.”

I’ve now assembled all 30 essays in this article. I hope you’ll read them and emerge with a deeper appreciation for the cell, atoms and their confluence with physics and math.

I scoured the internet for non-paywalled versions of each article, so all links go to open-source versions. This effort was inspired by the website “Read Something Wonderful.” Enjoy!

"I should have loved biology" by James Somers. An easy-to-read essay about how biology is poorly taught in schools, and how this poor teaching masks its most intriguing bits. Students are typically told to read textbooks and memorize facts about the cell (Mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell!) without ever appreciating its miraculous complexity. Tests are often given as multiple choice, with little to no problem-solving involved. As Somers writes: "It was only in college, when I read Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach, that I came to understand cells as recursively self-modifying programs." Link

"Cells are very fast and crowded places" by Ken Shirriff. A short essay about some awe-inspiring numbers in cell biology. My two favorite lines are: "A small molecule such as glucose is cruising around a cell at about 250 miles per hour" and "a typical enzyme can collide with something to react with 500,000 times every second." Link

"Seven Wonders," by Lewis Thomas. When Thomas was asked by a magazine editor “to join six other people at dinner to make a list of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World,” he declined and instead drafted this article about the seven wonders of biology. Number 2 on the list: Bacteria that survive in 250°C waters. Link

"Life at low Reynolds number," by E.M. Purcell. An all-time classic. One of the best biology lectures of all time. This essay opened my eyes to the weirdness of life at the microscale, where "inertia plays no role whatsoever." Or, as Purcell says, "We know that F = ma, but [microbes] could scarcely care less." Link

"The Baffling Intelligence of a Single Cell," by James Somers & Edwin Morris. This interactive article, about chemotaxis and flagella, gives "an intuition for how a bag of unthinking chemicals could possibly give rise to a being." It’s stunning and slightly emblematic of the great Bartosz Ciechanowski’s blog. Link

"Thoughts About Biology," by James Bonner. A little-read essay, I think, that deserves more attention. Published in 1960, Bonner argues that biology is ever-changing and progress, often, comes from those outside the field. Part of biology’s beauty is that you can push it forward regardless of background. Link

"Biology is more theoretical than physics," by Jeremy Gunawardena. It is often said "that biology is not theoretical," writes Gunawardena, but that's not true. This essay gives examples where theory preceded and informed major discoveries in biology. It’s a must-read, especially for those who want to work on biology but don't feel compelled to work at the bench with a pipette in hand. Link

"Can a biologist fix a radio?" by Yuri Lazebnik. One of my favorites. Biologists tend to catalog things by breaking them apart. But without quantitative insights, it is difficult to piece them back together into a holistic understanding. Even if you think a line of inquiry in biology has been exhausted, there is always room to go deeper. Link

"Schrodinger’s What Is Life? at 75" by Rob Phillips. In 1944, physicist Erwin Schrödinger wrote a book, called “What is Life?” that pondered a single question: “How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?" This essay is an ode, synopsis, and expansion of that classic book. "Names such as physics and biology are a strictly human conceit,” writes Phillips, “and the understanding of the phenomenon of life might require us to blur the boundaries between these fields." Link

"Molecular 'Vitalism'" by Marc Kirschner, John Gerhart & Tim Mitchison. Students are often taught that genes are the bedrock, or blueprint, for biology. But this picture is quickly changing, unraveling, fading. "Although...proteins, cells, and embryos are...the products of genes, the mechanisms that promote their function are often far removed from sequence information." Link

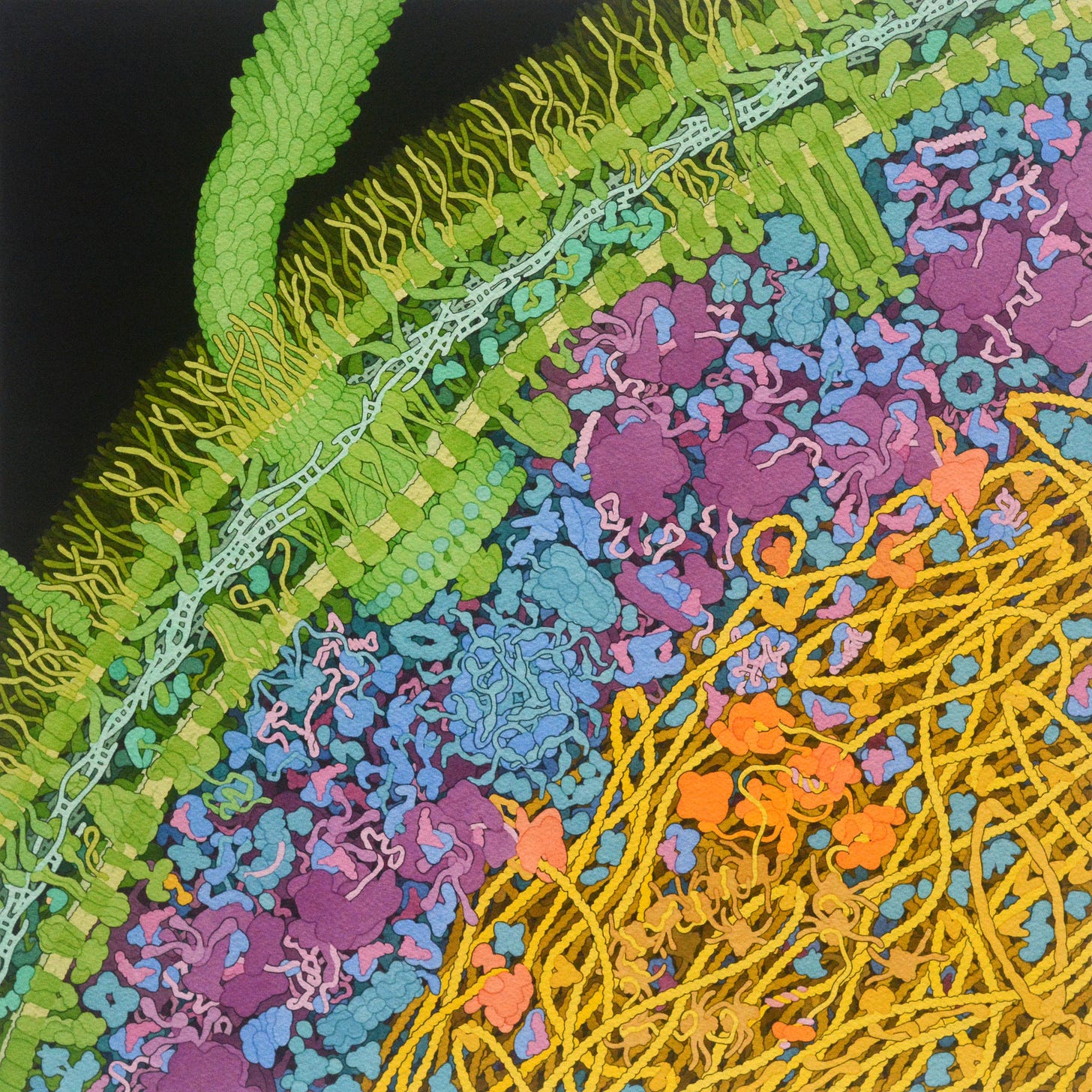

"Escherichia coli," by David Goodsell. Goodsell is a computational biologist who also makes brilliant watercolor paintings of living cells. His paintings are based on atomic truth—that is, the ribosomes, mRNAs, and DNA molecules are all painted to scale. This short essay explains how he does it. Link

"How Life Really Works," by Philip Ball. This essay challenges much that students are taught about how cells actually work. DNA is not some all-powerful blueprint of the cell, as textbooks often suggest. To truly understand life, argues Ball, one must first realize that cells are far more complex than that. They are, in fact, intelligent agents that change their surroundings to their own benefit. Link

"A Long Line of Cells," by Lewis Thomas. Another masterful essay that traces one man's life, and mankind's progress, through the lens of evolutionary biology. It helped me appreciate how my own life is deeply intertwined with the lives of organisms all around me. Link

"AlphaFold2 @ CASP14," by Mohammed AlQuraishi. Biological progress is swift, and that is one reason it is so exciting. In this first-person essay, a computational biologist marvels at a scientific breakthrough in predicting protein structures from their amino acid sequences. Link

"Theory in Biology: Figure 1 or Figure 7?," by Rob Phillips. Another great essay about theory—and not just wet-lab experiments—as a key driver of scientific progress. "Most of the time, if cell biologists use theory at all, it appears at the end of their paper, a parting shot from figure 7. A model is proposed after the experiments are done, and victory is declared if the model ‘fits’ the data." But such an approach is misguided, writes Phillips. As Henri Poincaré once said: "A science is built up of facts as a house is built up of bricks. But a mere accumulation of facts is no more a science than a pile of bricks is a house." Link

"On Being the Right Size," by J.B.S. Haldane. Published in 1926, this essay made me appreciate the myriad forms and functions of lifeforms all around me. I learned why an insect is not afraid of gravity; why a flea as large as a human couldn't jump as high as that human; why a tree spreads its branches, and much more. Simple, beautiful. Link

"I Have Landed," by Stephen Jay Gould. The final essay in a 300-essay series, Gould writes about how he often lies awake at night, pondering his purpose in the Universe and his fear of death. And how, upon deep reflection, he is most stunned by the fact that life—after more than 3.5 billion years of evolution—continues to exist at all “without a single microsecond of disruption." Link

"A Life of Its Own," by Michael Specter. Published in The New Yorker in 2009, this piece explores the then-nascent field of synthetic biology. It opens by telling the story of Jay Keasling, a professor at UC Berkeley, who engineered yeast to make an antimalarial drug called artemisinin, which has been used to save at least 7.6 million lives. Artemisinin was historically extracted from the sweet wormwood plant in a painstaking and low-efficiency process. Link

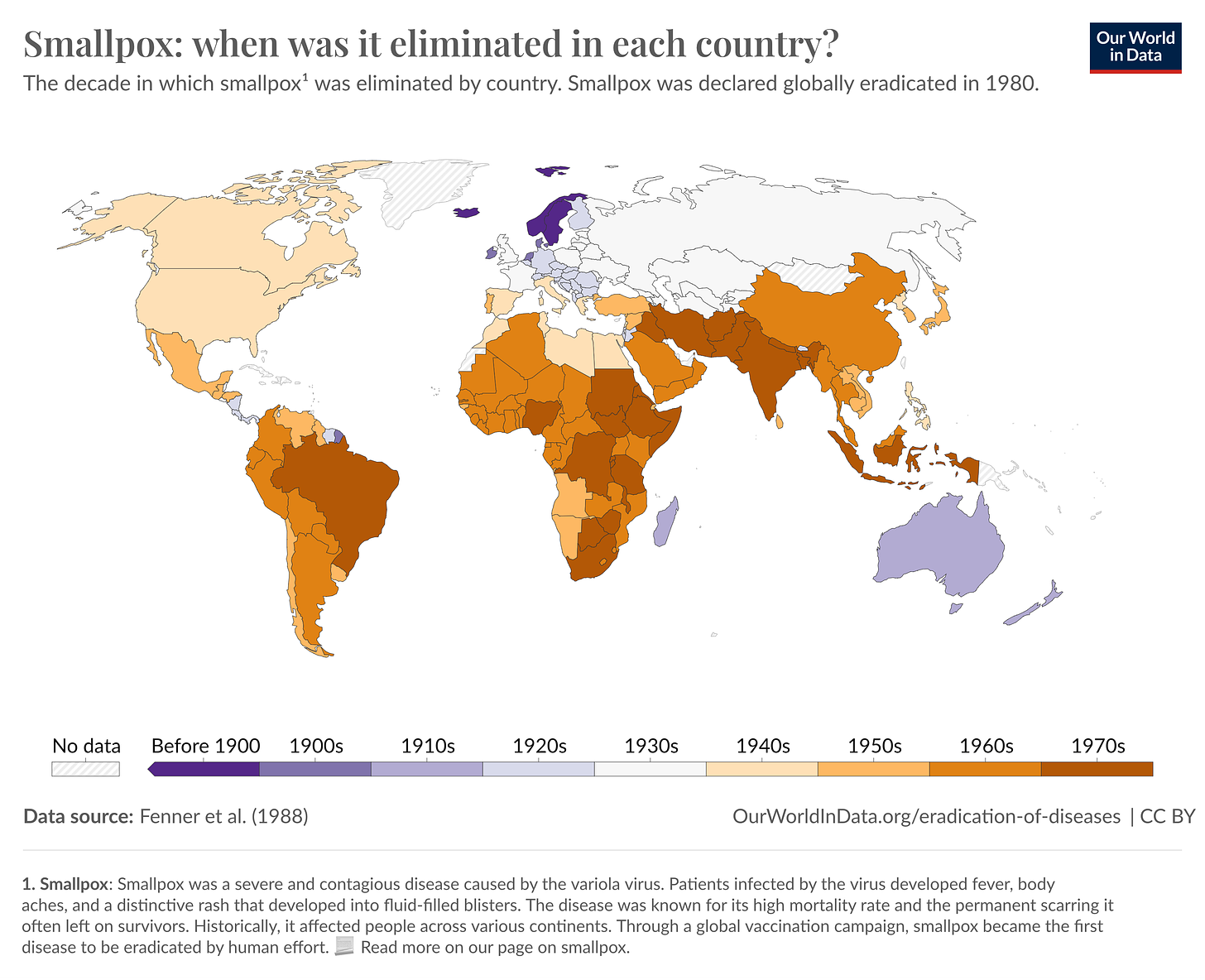

"Slaying the Speckled Monster," by Jason Crawford. Smallpox killed an estimated 300 million people in the 20th century alone. This essay explains how a long line of brilliant scientists—from John Fewster and Edward Jenner to D.A. Henderson—invented the first vaccines against the disease and then, in the 1960s, launched campaigns to eradicate smallpox entirely. An inspiring story about how biological discoveries can save lives. I also learned this: "The origin story [about smallpox vaccines] that is usually told, where Jenner learns of cowpox’s protective properties from local dairy worker lore or his own observations of the beauty of the milkmaids, turns out to be false—a fabrication by Jenner’s first biographer, possibly an attempt to bolster his reputation by erasing any prior art." Link

"Why we didn’t get a malaria vaccine sooner," by Saloni Dattani, Rachel Glennerster & Siddhartha Haria. Malaria has killed billions of humans in the last few centuries and continues to kill 600,000+ each year. This is, simply put, the best essay ever written on the history of malaria and the invention of vaccines to prevent it. We are living through a revolutionary time, considering these vaccines were only approved for the first time in 2021. Link

"Biology is a Burrito" and "Fast Biology," by Niko McCarty. Cells are often envisioned as wide-open spaces, where molecules diffuse freely. But this isn't true. In reality, cells are so crowded, it’s a wonder they work at all. Every protein in the cell collides with about 10 billion water molecules per second. Protein ‘motors’ make energy-storing molecules by spinning around thousands of times a minute. Sugar molecules fly by at 250 miles per hour, nearly double the speed of a Cessna 172 airplane at cruising speed. When I first heard these numbers, I thought they were made up. After all, how is it even possible to measure such things? The world’s most powerful microscope cannot necessarily “see” a protein motor spinning, or watch a sugar molecule move through a cell. As a PhD student, I jumped head-first into the world of biological speed. My goal was to collect some "remarkable" numbers in biology and understand the experiments that brought them to light. My search made me appreciate how remarkable it is that life functions at all, considering the chaotic conditions in which cells exist. It also gave me a new appreciation for biology, and the incredible exactitude that one must have to engineer it — let alone engineer it successfully. Link | Link

"Jonas Salk, the People’s Scientist," by Algis Valiunas. Salk made one of the first successful polio vaccines. A double-blind clinical trial, launched in 1954, showed that patients who received his vaccine "developed paralytic polio at about one-third the rate of the control groups. On average across the different types...the vaccine was eighty to ninety percent effective." Shortly after the trial's results were made public, journalist Edward R. Murrow interviewed Salk. When Murrow asked Salk who held the patent on the vaccine, Salk replied: “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?” Reading this essay helped me to appreciate the struggle and strife of biological research, the fickleness of fame, and the positive impact that a small group of scientists can have on the world. Link

"On Protein Synthesis," by Francis Crick. Arguably the most important essay in biology’s history, this was adapted from a lecture that Crick gave in 1957 during which the famed geneticist made several accurate predictions about how cells work well before experimental evidence existed to support them. “I shall…argue that the main function of the genetic material is to control (not necessarily directly) the synthesis of proteins," wrote Crick. "There is a little direct evidence to support this, but to my mind the psychological drive behind this hypothesis is at the moment independent of such evidence.” At the time, scientists weren't sure DNA had anything to do with proteins. In this essay, Crick also predicted the existence of a small ‘adaptor’ molecule that brings amino acids to the ribosome for protein synthesis (now known as tRNAs) and that future scientists would chart evolutionary lineages by comparing DNA sequences between organisms. Crick was years ahead of his time. This essay is a masterclass in scientific thinking. Link

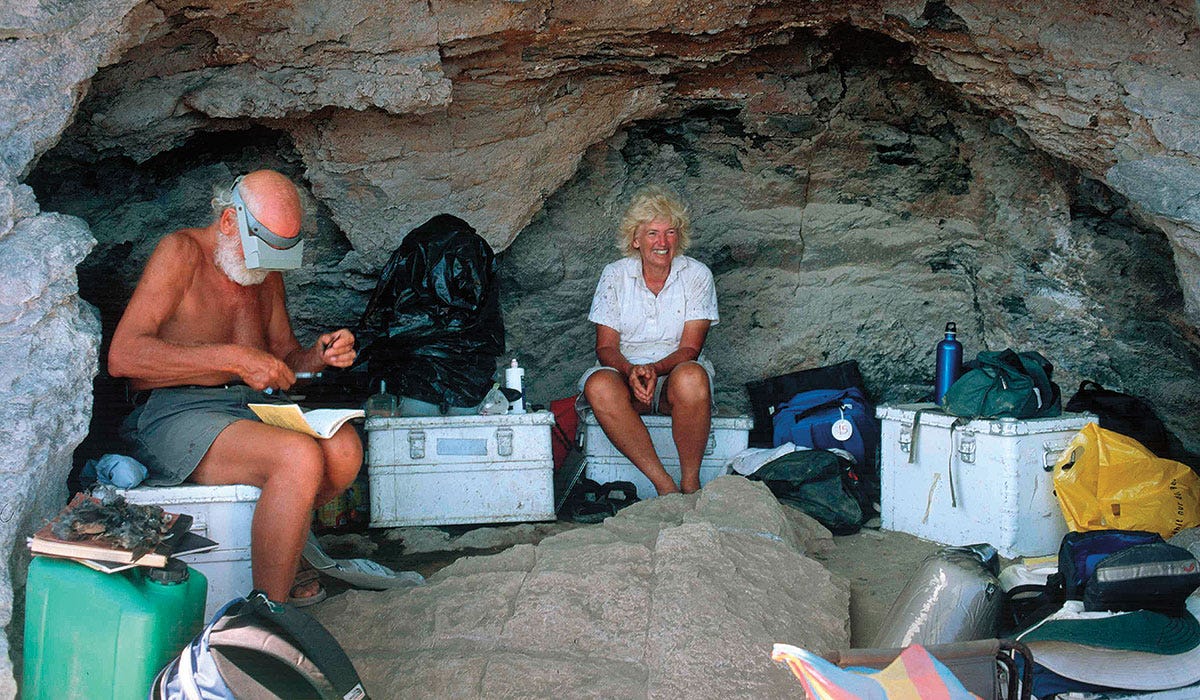

"The People Who Saw Evolution," by Joel Achenbach. My favorite article on this list. Every year, for 40 years, Peter and Rosemary Grant traveled to Daphne Major, a volcanic island in the Galápagos, to study Charles Darwin's finches. During that time, they watched "evolution happen right before their eyes." In 1977, for example, just 24 millimeters of rain fell on Daphne Major, causing major food sources—including small, soft seeds—to become scarce. When the Grants returned to the island in 1978, they found that smaller finch species had died off, whereas “finches with larger beaks were able to eat the seeds and reproduce. The population in the years following the drought in 1977 had ‘measurably larger’ beaks than had the previous birds." I also strongly recommend the book, “40 Years of Evolution,” from Princeton University Press. Link

"Is the cell really a machine?" by Daniel J. Nicholson. Living cells are far more complex—and beautiful—than any machines made by human hands. In this essay, a philosopher points to four areas of current research where the metaphor of "cells as machines" breaks down. For example: Even though proteins are depicted as static or unmoving molecules, they actually “behave more like liquids than like solids." Link

"Biological Technology in 2050" by Rob Carlson. "In fifty years,” writes Carlson, “you may be reading The Economist on a leaf. The page will not look like a leaf, but it will be grown like a leaf. It will be designed for its function, and it will be alive. The leaf will be the product of intentional biological design and manufacturing." This is a futuristic essay about the potential of manipulating atoms via living cells. Link

"Research Papers Used to Have Style. What Happened?" by Roger's Bacon. This is an ode to beautiful scientific writing. The essay draws from classic biology research papers to make its case. Link

"Night Science," by Itai Yanai & Martin Lercher. A personal essay about scientific discoveries that do not emerge from the scientific method as it’s taught in school, as told by two biologists. Perhaps it will inspire you to take up night science experiments of your own. Link

"Atoms Are Local," by Elliot Hershberg. Biology is the ultimate distributed manufacturing platform. Cells harvest atoms from their environments—air and soil—and rearrange them to build materials, medicines, and everything we need to live. Link

"The Mechanistic Conception of Life," by Jacques Loeb. This is the article that got me hooked on biology a decade ago. Written by one of history’s greatest biologists, it poses a number of questions that I suspect will keep scientists busy for many decades to come. "We must either succeed in producing living matter artificially,” writes Loeb, “or we must find the reasons why this is impossible." Link

What essays did I miss? Let me know in the comments and I’ll expand the list :)

This is such a great idea for a blog. I tend to read about health from a more big-picture, epidemiological/sociological point of view. I am looking forward to falling in love with the science behind it all over the next month ❤️